Now, that we got our Toyota HiAce we thought it might be a good idea to add more power to the vehicle: in form of an 8s EVE LF280K LiFePO4 battery and a Victron MultiPlus Compact 24/1600/40-16 inverter/charger. In the following, we describe our setup and the reason why we built it like this.

The Requirements

- The sustained output power of the inverter must be over

1'200W. - Charging via AC via EVSE or generator must be possible.

- Charging via alternator must be possible (but is not the norm).

- Charging of

60%of the battery (from 20% – 80%) via AC should take less than180min. - The installation should use the minimum amount of space possible.

- We should be able to use our existing Eve LF280K cells, thus limiting the overall current to

140A. - As the vehicle will not have a diesel heater, it should be possible to run a

150Winfrared heater for at least 3 * (4+2)h =18h(^=2'700Wh). - In addition, the battery should be able to run a refrigerator with an average power consumption of

50Wfor at least72h^=3'600Wh(next to other power consumption).

Design Considerations

- With a maximum current of 140A and a cable run length of 1.5m, we should plan with a cross section of at least

35mm2. - Basically, with Eve LF280K cells we have three choices regarding the battery size:

- 1* 4s (“12V”) Configuration

4 * 3.2V * 280Ah =3'584Wh

This would lead to a required nominal AC charge power of at least716.8W/hand a charge current of at least56A/h. - 2* 4s (“12V”) Configuration

2* 4 * 3.2V * 280Ah =7'168Wh

This would lead to a required nominal AC charge power of at least1'433.6W/hand a charge current of at least112A/h.

- 1* 8s (“24V”) Configuration

8 * 3.2V * 280Ah =7'168Wh

This would lead to a required nominal AC charge power of at least1'433.6W/hand a charge current of at least56A/h.

- 1* 4s (“12V”) Configuration

- The Victron MultiPlus Compact xx/1600VA inverter/charger provides enough sustained power output (while being smaller than the non-Compact edition). Depending on the voltage of the battery, this will slightly impact the amount of charge current.

- To charge the battery via the alternator we would need a DC/DC converter that depends on the battery configuration as well (either 12-12 or 12-24). So, let’s have a look at the battery first.

1* 4s (“12V”) Configuration

The smallest, lightest and cheapest configuration. But capacity requirements regarding the fridge are only fulfilled, if there are no other loads. In addition, the discharge current is relatively high (scratching the maximum discharge rate of 0.5C).

2* 4s (“12V”) Configuration

More complex setup, as each battery needs a separate BMS, which leads to the need of an aggregator for both batteries to correctly report SoC and calculate CCL and DCL. In addition, more cabling and fusing is required (and probably to a large bus bar). Comes with the advantage of having a redundant battery in case a single battery fails. Most expensive configuration.

1* 8s (“24V”) Configuration

Custom battery build needed, as there is not enough space for a typical 2 * 4 cells setup behind he seats. But, only a single BMS and thus less wiring is needed. Comes with a slight disadvantage of not having native 12V from the battery. This is actually not an isse, as all our DC devices also accept 24V. Cells can better balance voltage differences across a single 8s bank.

The Setup

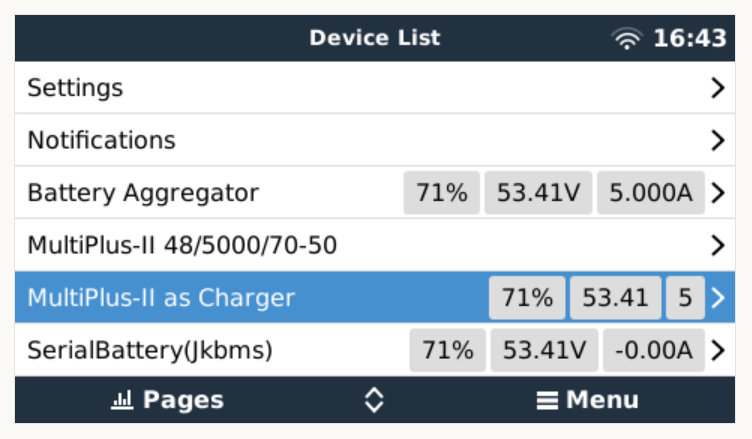

In the end, I decided for the 8s configuration, due to less complexity. Splitting the 8s configuration across two cell blocks seemed to be an acceptable compromise.

As a regular MultiPlus 24/1600/40-16 would not fulfill my AC charge requirements, I had to decide to either add a second MultiPlus or to add a dedicated charger. I opted for a Phoenix Smart IP43 Charger 24/25 instead of a second MultiPlus. The MultiPlus in parallel would always consume 10W though most of the time I would not need the output power. Whereas, the Phoenix would only need power, when connected to AC. And reconfiguring the MultiPlus every time I charge was not an option for me. And yes, I lose redundancy – but also save some money (Phoenix is much cheaper). So, in the end the nominal charge power is 40A + 25A = 65A, which lets me charge at 1'560W reaching 60% within 165min.

The HiAce comes with a 70A alternator, so I chose a Orion-Tr Smart 12/24-15 DC-DC Charger. With this charger, I could run the engine in standby and still have the car heater running. And this is probably the predominant use case (if charging via alternator at all).

For the DC bus bar I went for a Victron Lynx Distributor, so I could use and install MEGA fuses. Having a 1’000A bus bar seems certainly overkill, but a separate bus bar and fuse box that accepts 35mm2 cable and MEGA fuses would be not be much smaller.

I changed the existing AC inlet of the HiAce to Neutrik PowerCON True1 TOP (congrats to the marketing department, I am still amazed how this name rolls of the tongue) and installed 2 Siemens compact 16A C RCBOs (external AC in, internal AC out). I am aware that theoretically I could support more than 16A on the internal AC out (via PowerAssist). If ever needed, I can replace the RCBO with a 20A version.

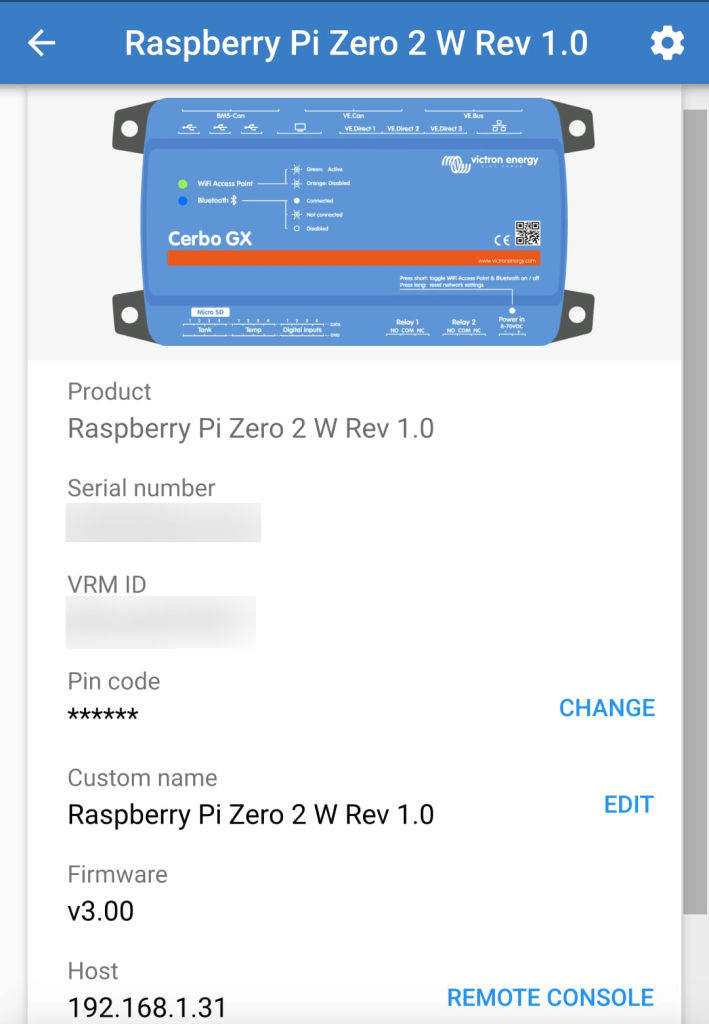

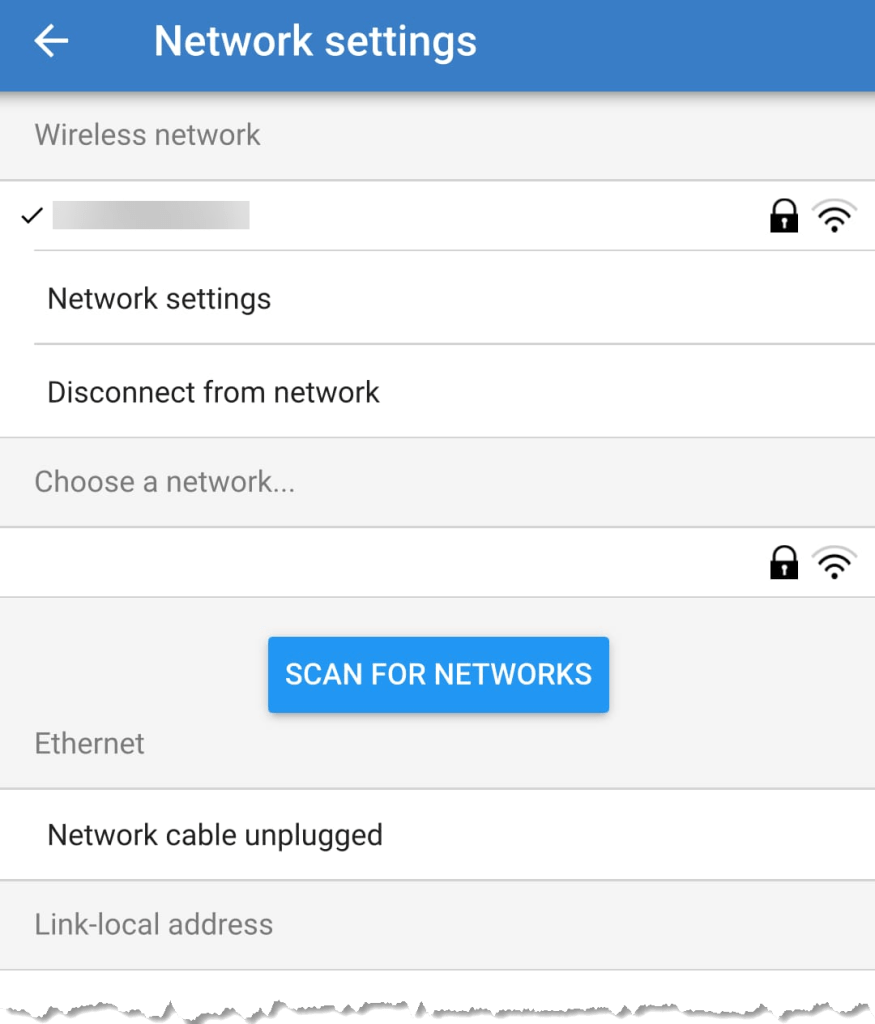

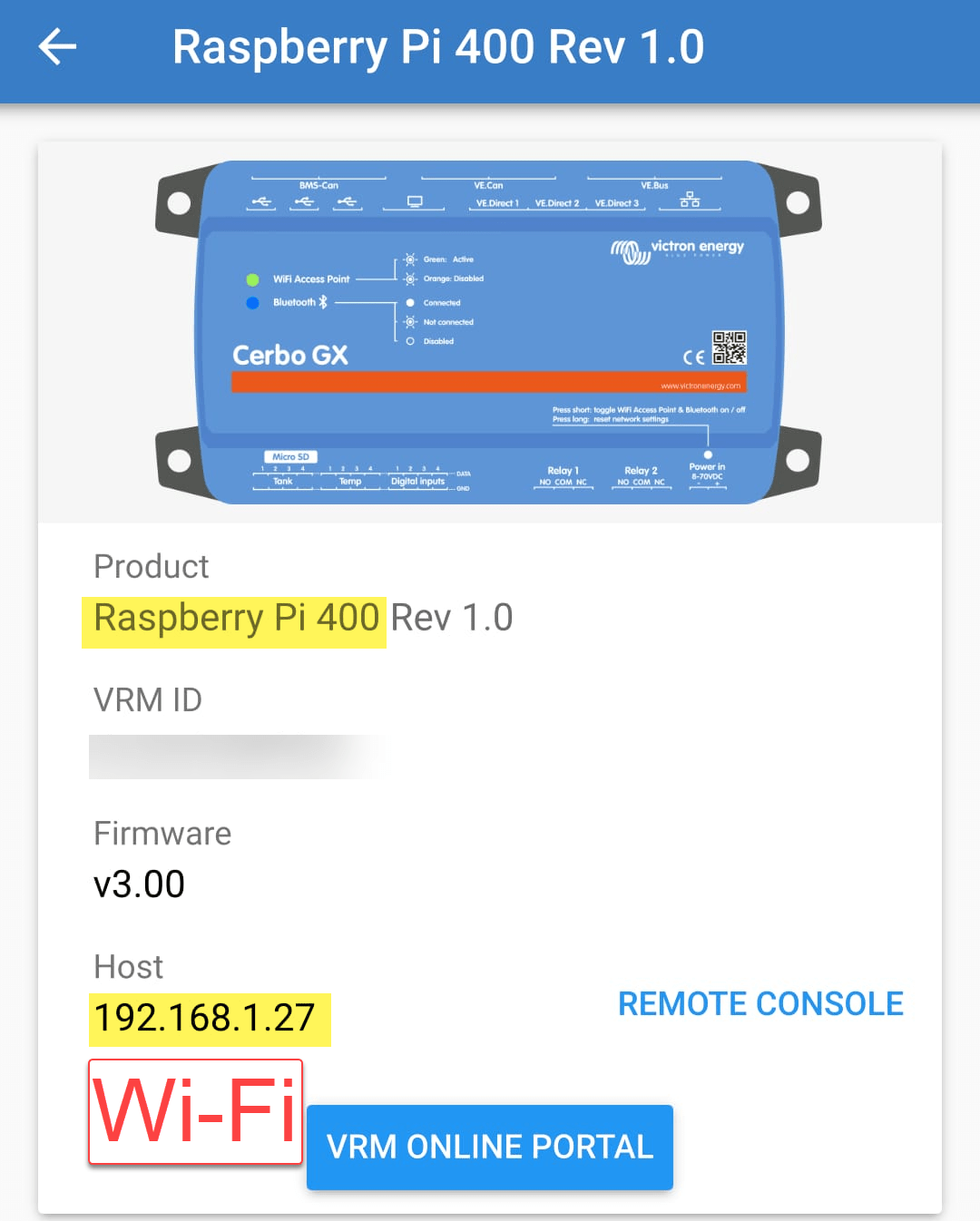

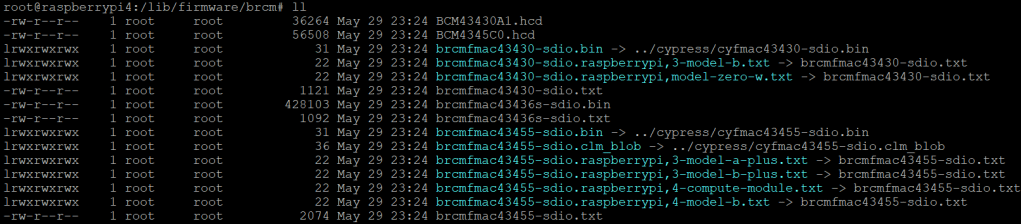

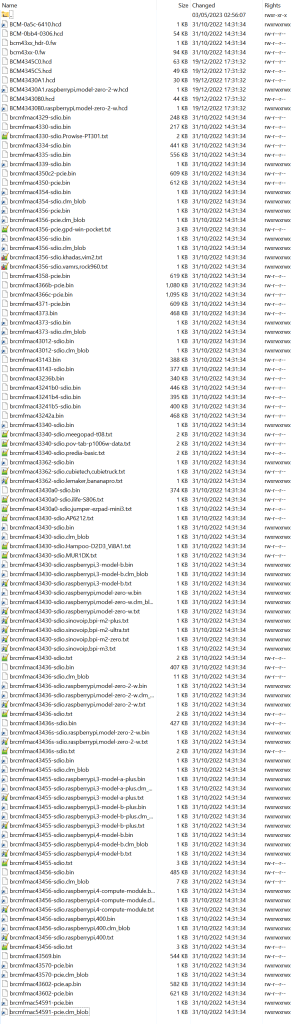

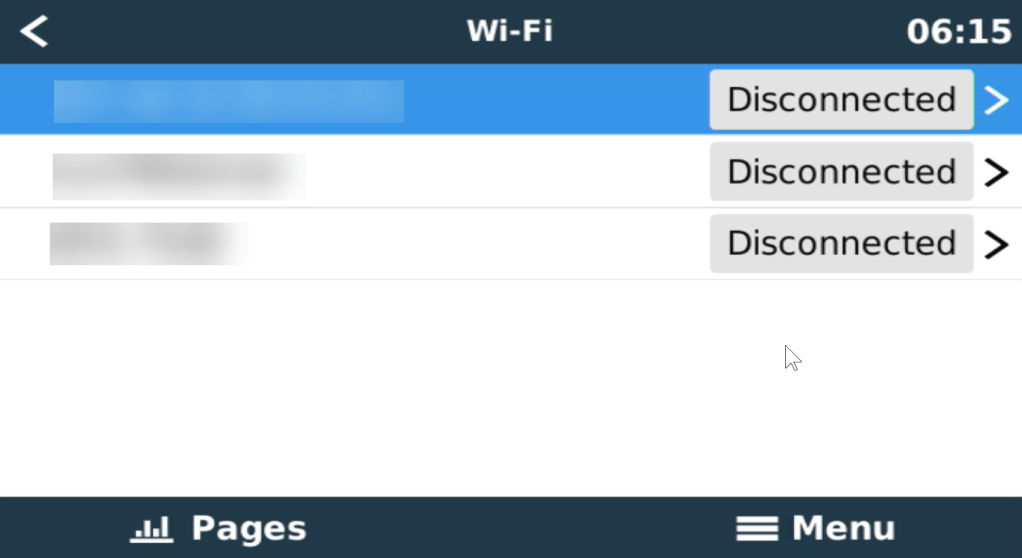

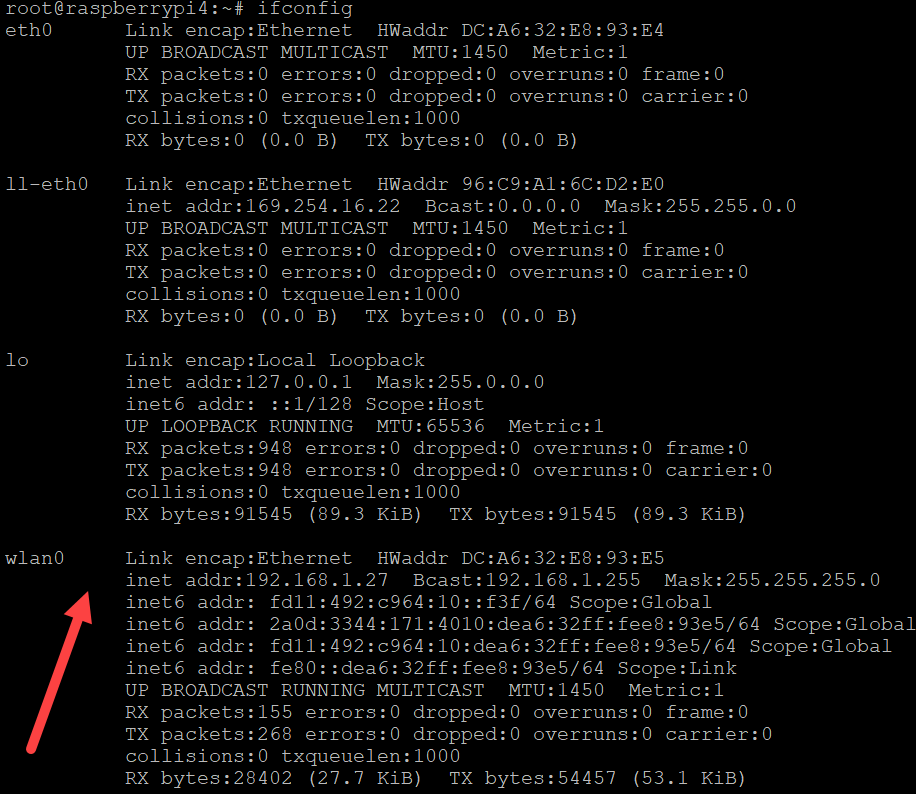

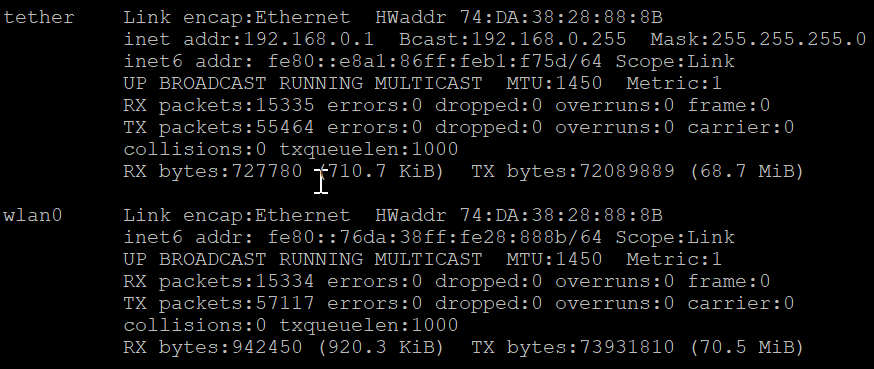

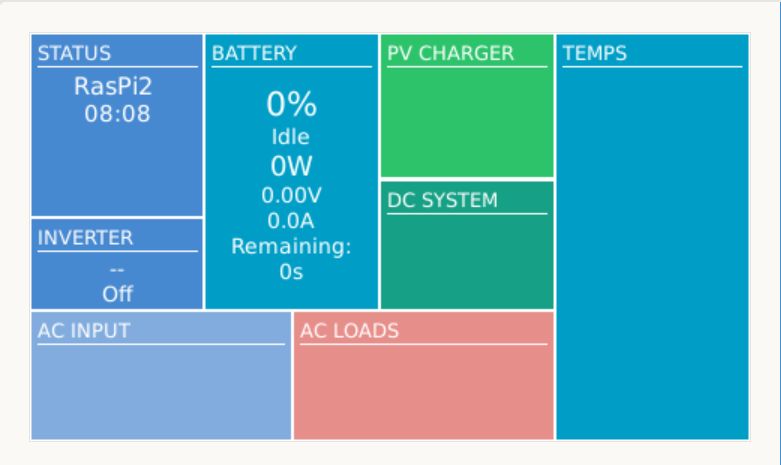

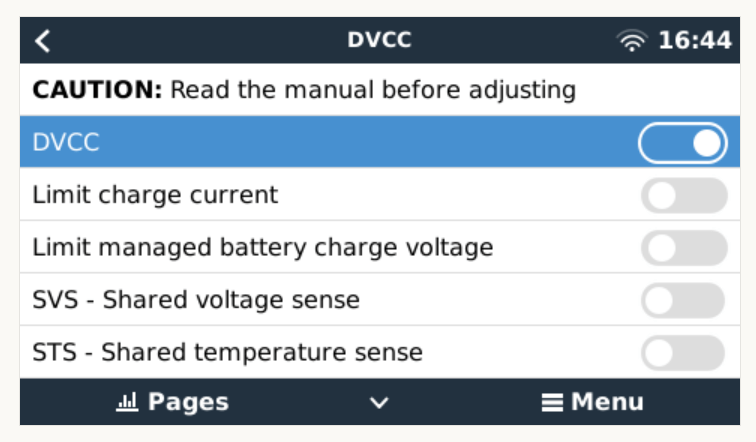

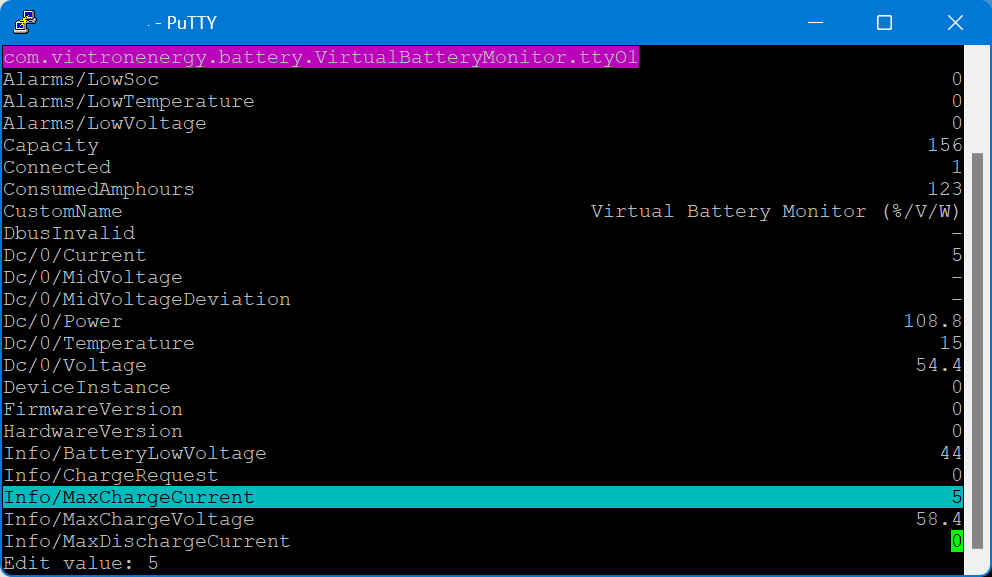

I added a VE.Bus Smart Dongle to the MultiPlus and opted against a complete (Raspberry-based) GX installation. The reason, I keep a USB MK3 with me anyway (in case I need to reconfigure the MultiPlus) and still have (Bluetooth) access to the most important settings and information of the MultiPlus. With the GX, I would to be running a WiFi hotspot (and consuming more energy as well). The disadvanage of not being able to use DVCC with information from the BMS is clear to me and accepted.

I selected a B2A8S20P JK-BMS that has an integrated 2A balancer and an RS485, CAN and heat port. In case, I ever add a GX device, I am still able to connect them and use DVCC.

The Specs

- Nominal power (“capacity”)

8 * 3.2V * 280Ah =7'168Wh - Maximum discharge power 1’600VA (

1'280W, capped by the inverter)

with a maximum current of 80A/63A/55A (at 2.5V/3.2V/3.65V) - Maximum AC charge power

1'560W - AC Charging from 20% – 80% in

165min - Maximum DC charge power

360W - MultiPlus self-power consumption 10W

The Build

As mentioned before, due to space constraints I had to split the battery in 2 parts (with each having 4 cells). Instead of using utz RAKO boxes I used 12mm (sanded) plywood which I did not screw together but tied down with a banding/tensioning tool and a ratchet strap. With this setup, I can easily access und disassemble the cells if needed, while still having a sturdy case. Both cell blocks are connected with a (blue) Anderson SB175 connector.

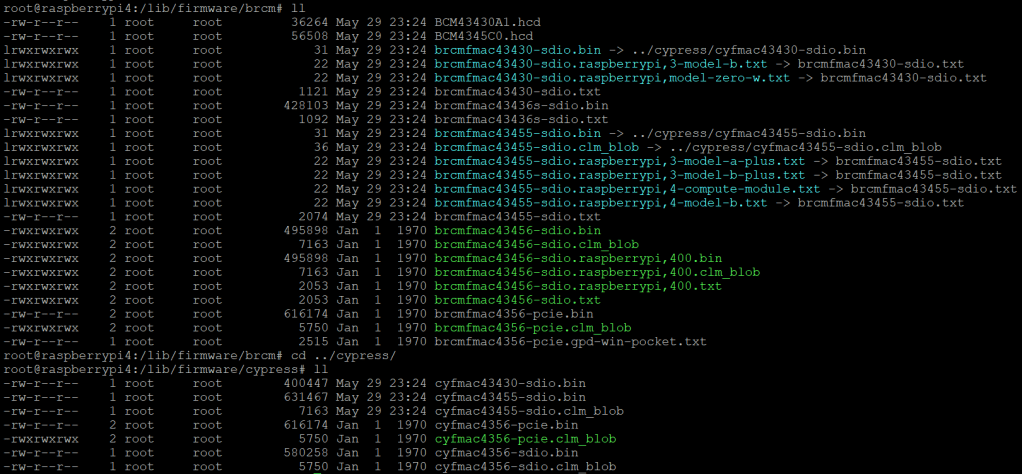

The BMS itself is mounted to the side of one of the cases (I took extra care to use short screws, in order not to drill into the cell casing). I used M6 Weidmüller 35mm2 90° angled compression cable lug to get the wire away from the BMS and into the bus bar. All other compression cable lugs are DIN 46235 from Klauke (M6 35mm2 on the cells, and M8 16mm2/35mm2 on the bus bar).

The AC and DC wires are all Eland H07RN-F (except for the last two points):

- Charger to bus bar, battery to bus bar:

35mm2 - Cell block to cell block:

2 * 35mm2 - Alternator to DC-DC converter, DC-DC converter to bus bar:

16mm2 - External AC in to RCBO, RCBO to inverter/charger (both directions), RCBO to internal AC out:

3G2.5mm2 - For the balancer cables on the cell blocks I used WAGO 221 inline splicing connectors with levers and bullet connectors with

2.5mm2wire and M6 ring terminals. - For the connection of the Inverter/charger to the bus bar, I used the Victron installed

25mm2welding cables.

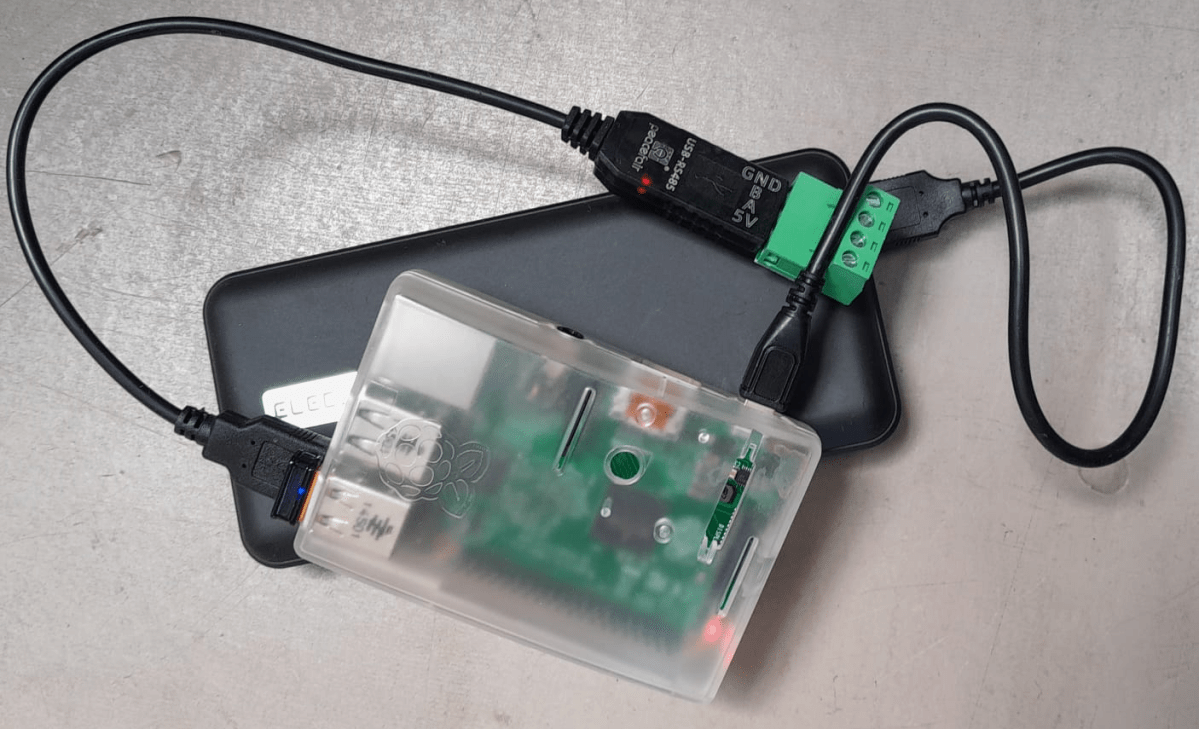

Images

Note: the Phoenix charger is not visible on the images, as I am still waiting for it to be delivered.

Conclusion

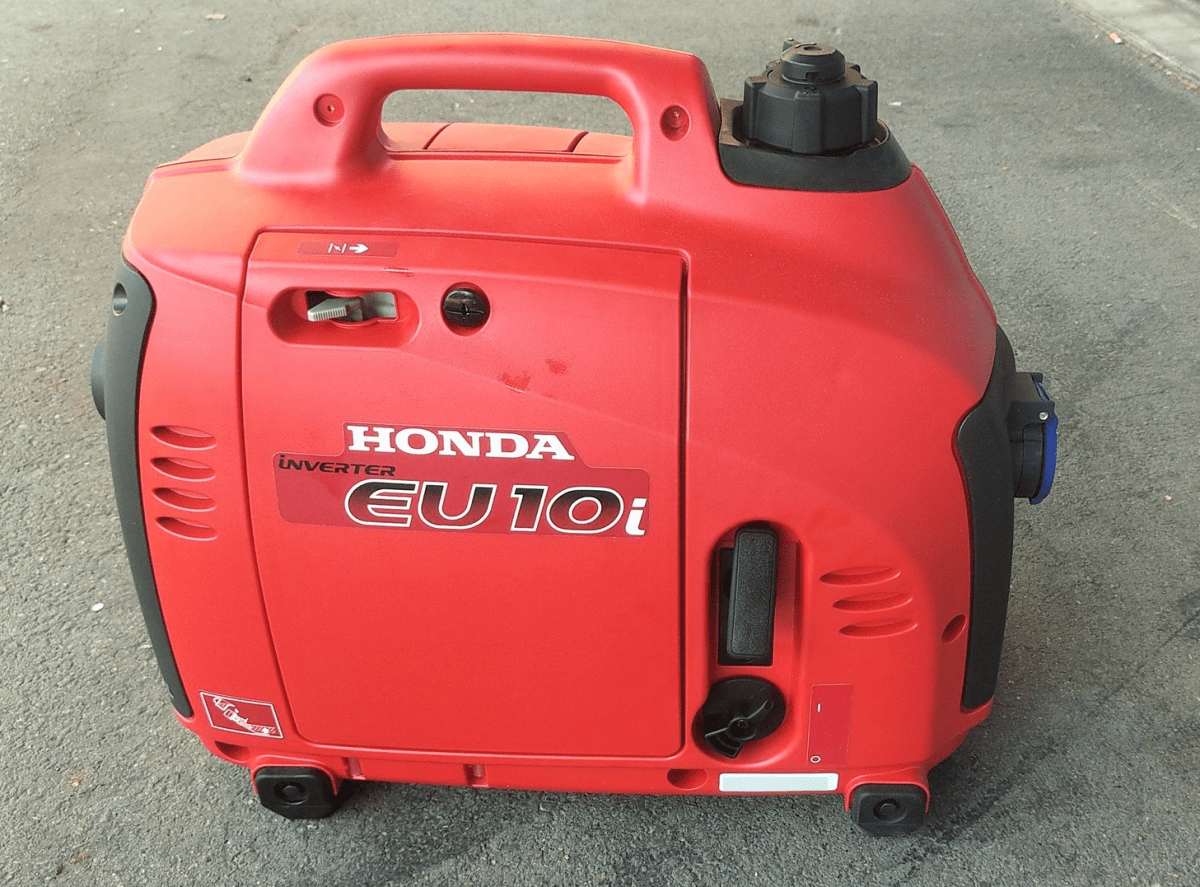

We now have more than 7'000Wh of additional energy without losing any storage space for roughly 2'850 CHF/2’500 GBP (parts without labour). We can survive an extended weekend of 72h without recharging while still being able to enjoy amenities as using a coffee machine, heating and refrigerator. In case of longer periods of usage, we can recharge at any EVSE, or via shore power. And in emergencies, we can also charge via our Honda EU10i or via the alternator of the vehicle.

The battery is placed directly over the engine which helps in cold weather conditions to easily warm up the batteries to a chargeable level.

The installation can be monitored via Bluetooth (Victron Connect and JK-BMS app).